Lawn Armyworm in Australia: Identification, Damage, Prevention and Treatment Guide.

Lawn armyworm (Spodoptera mauritia) is the most destructive warm-season turf pest in Australia, capable of stripping couch, kikuyu and ryegrass overnight.

The first signs of damage are scalloped turf edges, thinning cover, and small areas of window-paning. Large larvae can eat whole leaves and leave patches that brown off within hours.

These outbreaks are common in the late summer and the early autumn across Australia, especially on irrigated couch, kikuyu, and ryegrass surfaces.

Lawn Armyworm Identification.

The key to identification is colour, stripes, head shape, lifecycle and behaviour.

- Early larvae are small.

- They are pale and have fine stripes.

- Mid larvae are dark with more obvious bands.

- Mature larvae are much thicker, patterned caterpillars.

- They are 20 to 30 mm long, and when you disturb them, they curl into a tight “C” shape.

- They feed mainly at dusk and in the evening. This means you are best to check for activity at night or carry out a simple soapy-water flush.

- Damage tends to appear first on edges, goal mouths, field banks, and irrigated hot spots.

Lawn Grub vs Lawn Armyworm.

-

In Australia “Lawn grubs” are root-feeding beetle larvae. These are also known as curl grubs or scarab beetle larvae.

-

In contrast armyworms are leaf-feeding caterpillars that strip the foliage above the ground.

Both of these pests cause similar damage to turf, but where the damage occurs tells you which pest you have.

Lawn Grubs.

The lifecycle of the lawn grub is eggs to Larvae (curl grubs) to Pupae and then they become an adult beetle.

Where they feed:

-

Below the surface. They chew roots and stolons, and seldom shred leaves.

Key signs:

-

Turf lifts easily like a loose carpet.

-

Grass dies from the roots upward.

-

Birds dig at the turf to pull the larvae out.

-

Damage develops much more slowly compared to armyworm.

Appearance:

-

Lawn grubs are a White, C-shaped grub with a brown head and have six legs near the front of their body.

What Armyworms Are

The armyworm lifecycle comprises eggs to Larvae (these are the caterpillars) to Pupae and they then become a Moth.

Where they feed:

-

These feed above the ground. They chew leaves and stems.

Key signs:

-

Damage tends to be seen as the leaves have scalloped edges or are shreddedand you can see window-pane damage.

-

Turf tends to rapidly brown off. This sometimes happens overnight.

-

You see larvae on the surface, especially at dusk.

-

The moths fly around lights. You find egg masses on walls and fences.

Appearance:

-

A smooth caterpillar with yellow/white/dark stripes.

-

Larger larvae curl into a tight “C” if you handle them.

Damage Speed

| Pest | How fast they destroy turf | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Armyworm | Hours to overnight | Entire leaves are eaten, with big dead patches appearing suddenly. |

| Lawn grub | Days to weeks | Root damage, turf declines steadily, not instantly. |

Which Pest Do You Have?

| Symptom | Armyworm | Lawn Grub |

|---|---|---|

| Damage appears overnight | Yes | No |

| Brown patches start at edges/hotspots | Yes | Sometimes |

| Shredded or window-paned leaves | Yes | No |

| Turf lifts up easily | No | Yes |

| You can see caterpillars visible on the surface | Yes | No |

| Birds dig up turf | Sometimes | Common |

| You can see egg masses on walls or fences | Yes | No |

Lawn Armyworm Geography.

Armyworm outbreaks are common in the warm and humid regions of Australia. You see them most often across coastal and sub-coastal QLD, northern and central NSW, the ACT, and parts of VIC in the late summer and the early autumn.

Field observations show a repeat pattern of peak feeding pressure after hot spells and irrigation. This pattern has been seen consistently across NSW and QLD on couch, kikuyu, and ryegrass sports surfaces.

Why Lawn Armyworm Cycles Boom in El Niño and La Niña Years.

Armyworm populations rise sharply during both El Niño and La Niña, but this is for different reasons. In Australia, these climate phases shift temperature, humidity, and rainfall patterns, and directly accelerate the insect’s lifecycle and survival.

In An El Niño Heat Drives Outbreaks.

In an El Niño the temperature increases, rainfall falls, there are more frequent heatwaves and there is an increase in turf irrigation. These conditions cause armyworm outbreaks because higher temperatures accelerate development.

In an El Niño summer there is a rapid GDD accumulation. This causes:

- Eggs to hatch faster.

- Larvae to grow quicker and reach a damaging size earlier.

- There to be more generations over a season. El Niño summers often have 2 to 3 overlapping generations, in contrast to the usual 1 to 2.

Drier weather increases moth activity.

Moths fly further and more consistently in dry, warm air. This increases:

- Egg-laying across larger areas.

- The number of egg masses on walls, fences, and light structures.

Irrigation creates “green islands”.

When rainfall falls, irrigated turf becomes the best food source in the area. Armyworms tend to target:

- Ovals.

- Golf fairways.

- Parks.

- Sportsgrounds.

These irrigated areas sustain fresh leaf tissue, and draw in adults from the surrounding dry environments.

La Niña Years. Moisture-Driven Outbreaks.

La Niña causes higher humidity, above-average rainfall and increased cloud cover and warm nights. This produces a different set of conditions that favours armyworms.

High humidity Increases egg and young larvae survival.

Egg masses desiccate easily in dry weather. In a La Niña:

- Moisture protects the egg masses.

- Young larvae avoid early-stage mortality.

- More larvae reach large, damaging stages.

Warm nights accelerate feeding.

Armyworms feed intensively at night. At night during a La Niña:

- Conditions stay warm for longer.

- There is an increase in the hours of continuous feeding.

- This causes an increase in the rate of leaf loss and more severe outbreaks.

Heavy rain causes flushes of new turf growth.

New growth means an increase in food for armyworms.

Sports turf often:

-

Recovers rapidly.

-

Then gets hit again.

-

This leads to multiple “waves” of damage within a single La Niña season.

More vegetation means there are more egg laying sites.

Rapid plant growth around turf facilities (banks, fence lines, unmaintained surrounds) increases egg-laying surfaces.

Why Both Climate Patterns Increase Risk.

| Climate Phase | Main Driver | Result |

|---|---|---|

| El Niño | Heat + irrigation | Fast life cycles and multiple generations |

| La Niña | Moisture + warm nights | High survival + more feeding hours + recurrent waves |

In short:

-

El Niño ≈ faster cycles.

-

La Niña ≈ higher survival + heavier feeding.

Both lead to boom years, but due to different biological mechanisms.

Field Observations from NSW & QLD Turf Sites (2018–2024).

Across couch, kikuyu, and ryegrass surfaces:

-

In El Niño seasons after heatwaves there tend to be high-intensity bursts of armyworm feeding.

-

La Niña seasons produce persistent, long-running infestations, with repeat peaks after rain events.

-

Irrigated sports turf always acts as a magnet for adult moths under both patterns.

-

Multi-generational overlaps are common in both conditions. However the causes differ (heat vs survival).

How Climate Phases Influence the GDD Model.

El Niño.

GDD accumulates rapidly so that predicted larval peaks arrive earlier.

La Niña.

GDD accumulates normally, but:

-

Egg survival rates rise.

-

Feeding hours extend.

-

Larval populations grow outside normal heat thresholds.

This produces unexpected late-season spikes, especially in humid autumn periods.

How To Predict Lawn Armyworm in Australia.

Temperature controls the development rate of the Armyworm, which makes it ideal for heat-based modelling.

- A growing degree day (GDD) model measures how much heat the insect receives once the eggs are laid.

- Each life stage needs a set amount of heat to develop. In Australia, Lawn Armyworm completes a single generation in about 500 GDD above a 12 °C base.

- This GDD threshold (522 GDD base 10°C) is based on Australian field observations taken from NSW and QLD sports fields between 2018 to 2024.

- If you track the heat from a “biofix point”, you can estimate egg hatch and early larvae stages.

- By doing this it also shows when large late stage larvae will begin to cause damage. This gives a clear warning window in comparison to visual scouting.

This model removes guesswork, reduces waste, and helps you match the right product to the correct growth stage. Our Lawn Armyworm Predictor uses local temperature data, and gives you a practical forecast.

Biofix Date.

A biofix date is when you first see a clear events such as egg masses, early larvae, or an increase in moth flights. Once you set the biofix date, the model uses BOM max and min temperatures to calculate the daily GDD totals and predict the life stage.

How to Monitor For Lawn Armyworm.

- If you regularly monitor it prevents you having any nasty surprises.

- Check the turf edges and lights for moth flights.

- Search for egg masses on posts, fences, and nearby plants.

- Use a soapy-water drench to flush any larvae out of the thatch.

- Watch for thinning turf areas, ragged leaf tips, and rapid browning.

If you combine field checks with this model it gives a much clearer picture of any risk. This then allows you to carry out any treatment before large areas of turf are lost.

Prevention.

Prevention helps limit damage.

- Maintain adequate turf nutrition to help with strong recovery.

- Reduce thatch levels where possible.

- Keep your height of cut consistent.

- If any damage occurs, irrigate and apply light rates of N to help with recovery.

- Where turf density drops, refer to our integrated lawn weed management guide to prevent opportunistic weed invasion.

- Maintaining adequate soil moisture uniformity helps limit stress. Tools like the Soil Wetting Agent Selector assist with consistent infiltration.

- These steps support plant health and help the turf rebound after damage.

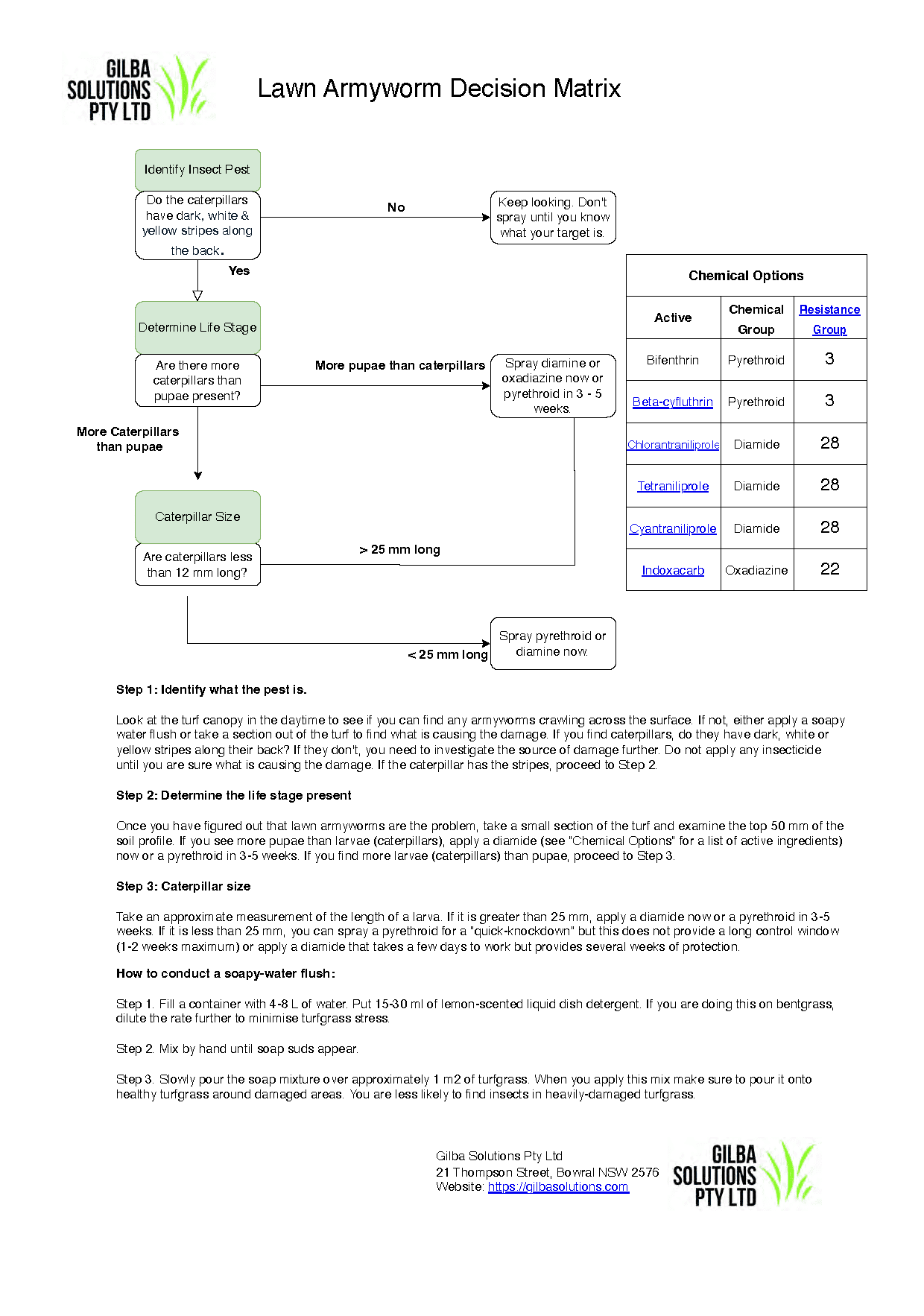

Lawn Armyworm Treatments and Growth Stage.

You need to use different products to control early larvae than for large larvae or pupae. If you match your chemical use to the growth stage it increases your success and reduces waste.

Timing.

- The best time to treat this pest is when they are young larvae. These respond the best to diamide insecticides.

- These will continue to work on mid larvae but at this stage you can also use indoxacarb.

- Once they become larger you will start too see damage and at this stage you need to use a pyrethroid for a quick knockdown.

Control involves good timing and the use of the right products. Early intervention is always more effective.

Insecticide Resistance Management.

- Group 28 (diamide) insecticides give long residual protection and are ideal for early to mid larvae.

- You can use Group 22A (indoxacarb) in the mid stages.

- Group 3A (pyrethroid) insecticides give a rapid knockdown when large larvae are present.

If you use the right selective, rotate MOA groups, and make sure that you follow the label it reduces the resistance pressure and improves your long-term control.

This GDD model does not replace physical checks, but it gives a clear warning window well before any damage will appear in the turf.

This is especially useful on sports fields and top tier lawns that rely on uniform cover and cannot afford any sudden loss of grass.

The ‘KISS’ System For Lawn Armyworm.

- The approach is simple. Warm days mean faster development. Cool days mean slow development.

- If you look at the amount of accumulated heat rather than the calendar date, you get a much clearer picture of the risk.

- Daily temperature inputs for Lawn Armyworm modelling can be drawn directly from the Bureau of Meteorology. The model uses BOM maximum and minimum temperatures to calculate degree-days above the 12 °C base.

- This gives a more accurate, site-specific estimate than seasonal averages.

- Most sports turf managers already use BOM data for irrigation planning or heat-stress risk.

As a company Gilba Solutions fully supports the development of predictive models and in 2025 we have launched several such as the Argentine Stem Weevil Predictive Model and the Soil Compaction Model to help turf professionals and lawn owners.

For Lawn Armyworm, the goal is early detection and early action. This model gives turf managers a practical way to stay ahead of an insect that can cause severe damage in a short period of time.

Common Mistakes People Make With Lawn Armyworm.

- Spraying late-stage larvae too late.

- Mowing too low after damage.

- Relying on pyrethroids too early.

- Not checking for egg masses after treatment.

- Watering immediately before spraying.

- Assuming that any brown patches are the result of armyworm. More often than not they are the result of drought or a hydrophobic soil.

Lawn Armyworm GDD Predictor

Growing degree day model for armyworm lifecycle prediction and spray timingModel Stage Bands

Disclaimer, Model Limitations & References

This tool provides estimates only and must not replace professional agronomic advice or product label directions. Always read and follow the registered product label.

Model limitations: GDD models assume a linear relationship between temperature and insect development rate. Field conditions can shift actual development timing. The Modified Average Method is used with species-specific developmental thresholds. Multi-generation tracking resets GDD at each generation boundary — in practice, generations may overlap.

S. mauritia note: No peer-reviewed GDD thresholds exist for lawn armyworm. This model uses thermal requirements from the closely related S. litura as a proxy (Ranga Rao, G.V., Wightman, J.A. & Ranga Rao, D.V. (1989). Threshold Temperatures and Thermal Requirements for the Development of Spodoptera litura. Environmental Entomology, 18(4), 548–551). Larval sub-stage bands (early/mid/late) are proportional estimates only. Use this model as a guide, not an absolute predictor.

S. frugiperda data: Base temperature 12.6 °C, egg 36 DD, larval 205 DD, pupal 151 DD, total ~392 DD (Du Plessis, H., Schlemmer, M.L. & Van den Berg, J. (2020). The Effect of Temperature on the Development of Spodoptera frugiperda. Insects, 11(4), 228). Du Plessis data was selected as the more rigorous and widely cited study, but Australian FAW populations arrived from Southeast Asia and may differ. S. frugiperda distribution: Fall armyworm is established year-round only in tropical/subtropical Australia (northern QLD, NT, northern WA — approximately north of 20°S). It occurs seasonally (spring–autumn) in the subtropics (~20–28°S) and as an occasional migrant further south. It is NOT established in temperate southern Australia.

GDD methodology reference: The Modified Average Method follows McMaster, G.S. & Wilhelm, W.W. (1997). Growing degree-days: one equation, two interpretations. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 87(4), 291–300.

Gilba Solutions Pty Ltd. Tool version 2.1.0. For decision support only — not a substitute for professional pest management advice.

References.

Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries (DAF): Armyworm and pasture pest updates.

IRAC (Insecticide Resistance Action Committee): Mode of Action Classification Scheme.

Australian Turfgrass Management Journal: seasonal pest behaviour reports.

Bureau of Meteorology (BOM): Climate Data Services for Tmax/Tmin records.

Armyworm FAQ

What do lawn armyworm eggs look like?

Egg masses appear as cream to pale-brown clusters on walls, posts, fences, sheds, and eaves. They resemble small fuzzy patches or flattened pads and are often laid near outdoor lights. They may appear moist when fresh and dry to a papery texture as they age.

How can I prevent lawn armyworm infestations?

Maintain healthy turf, reduce any thatch to acceptable limits, don’t vary your heights of cut, and monitor for moth activity. If you see any egg massesremove them and use predictive tools or models (e.g., the GDD-based Lawn Armyworm Predictor) to anticipate any outbreaks.

Will my lawn recover after armyworm damage?

Yes your lawn will most likely recover after armyworm damage. Water the damaged area, maintain good nutrition, and do not scalp the turf when you mow. Couch, kikuyu, and ryegrass usually recover if you treat them early. However if there is severe damage you may need to overseed or repair areas. See the overseeding guide.

Lawn armyworm mainly removes leaf tissue. This means that most warm-season grasses will recover as long as the growing points are not damaged. Couch, kikuyu and buffalo grass will all recover well once they receive moisture, warmth, and nutrition. Perennial ryegrass also recovers, although severely grazed patches may need to be overseeded.

Recovery Depends on How Much Leaf They Remove.

-

If there has only been light to moderate feeding and only the upper canopy appears to be shredded or window-paned. Rapid recovery is often within 7 to 14 days.

-

When there has been heavy feeding, and large larvae have removed most leaves but the crowns remain alive. Recovery takes 3 to 5 weeks and requires irrigation + small light N applications.

-

If there has been extreme defoliation, and the crowns and stolons are damaged and there are dry, bleached patches. Some areas will recover. Other areas may need oversowing or re-turfing.

Species Differences in Recovery Time.

Couch (Bermuda).

Excellent recovery due to stolons and rhizomes. Needs warm weather and irrigation.

Kikuyu.

Very strong regrowth potential under warm conditions.

Buffalo (St Augustine).

Recovers much more slower than couch or kikuyu because it only has stolons. It still regrows well in warm weather.

Perennial Ryegrass.

Will recover well if the crowns remain intact. Severe damage may require overseeding to restore turf density.

Fine Fescues.

Recover slowly and are more prone to thinning after heavy feeding.

Season Influences Time To Recover.

Late Summer / Early Autumn (peak activity).

Warm soil and residual heat allow the turf to rapidly regrow. This is the best recovery window possible.

Late Autumn / Early Winter.

Cool weather slows recovery dramatically. At this time of year recovery may take until the Spring.

Mid-Winter (for cool climates).

Little to no recovery until the soil warms up.

What You Must Do Immediately After Armyworm Damage

Irrigate Lightly and Consistently.

Moisture encourages new leaf production and helps the turf recover from heat stress and feeding loss.

Apply a Light Rate of N.

A small application (e.g. 5–10 g N/m²) encourages new leaf growth without encouraging excessive thatch.

Remove The Armyworm First.

Recovery will not start until all larvae are controlled. Continue monitoring for 7 to 10 days for late hatchings.

Avoid Scalping.

Retain as much green leaf as possible to maximise photosynthesis.

Repair Bare or Dead Spots.

For severely grazed areas:

-

Couch/kikuyu: verticut or groom and irrigate

-

Ryegrass: overseed

-

Buffalo: plug or re-turf if stolons are dead

Timeline for Recovery

Fast Recovery (7–14 days).

-

Light feeding.

-

Warm temperatures.

-

Adequate moisture.

-

Turf with stolons/rhizomes (couch, kikuyu).

Moderate Recovery (3–5 weeks)

-

Heavy canopy loss.

-

Cool autumn periods.

-

Recovery dependent on nutrition + irrigation.

Slow Recovery (6–10 weeks or longer).

-

Late autumn feeding.

-

Turf already under stress.

-

Damage all teh way down to the crowns.

-

Fine fescues or ryegrass without any overseeding.

When Will Turf Not Recover?

Recovery may fail if:

-

Crowns and stolons have been eaten or are desiccated.

-

Turf was already under stress (drought, shade, compaction).

-

Feeding happens late in the season and temperatures drop suddenly.

-

Water was limited after the outbreak.

-

Cool-season turf was eaten heavily without follow-up overseeding.

In these cases, targeted renovation is required.

Professional Observation From Australian Turf Sites.

Across NSW and QLD sports fields (2018–2024):

-

Areas treated early recover fully without renovation.

-

Late detection led to severe thinning in ryegrass and buffalo.

-

Couch and kikuyu recover most reliably, especially with irrigation + light N.

-

Autumn feeding under La Niña conditions often produces multiple waves of damage.

How fast can lawn armyworm damage a lawn?

Large larvae can strip turf within hours, especially during warm nights. Entire patches can brown off overnight, which makes early detection essential.

What is the best treatment for lawn armyworm?

The best treatment for lawn armyworm is to make sure that you target any chemical application to match the larval stage of the armyworm.

-

For early larvae. Use Group 28 insecticides (diamides). These give the longest residual, and have the highest success rate.

-

For mid larvae. Use the diamides or Group 22A insecticides like indoxacarb.

-

For large larvae. For the large larvae use Group 3A pyrethroids for a fast knockdown.

Treat early for better control and always rotate IRAC groups.

How can I confirm lawn armyworm is present?

It’s best to check the turf in the evening to see if armyworm are present. Inspect the turf edges and lights for moths. Look for egg masses, and flush the turf with a soapy-water drench (dish detergent + water). If any larvae are present they will come to the surface within minutes.

What causes lawn armyworm outbreaks?

Warm temperatures speed up development, and cause a rapid increase in larvae numbers. The moths lay their egg masses on walls, fences, and vegetation, and the larvae then hatch and move onto the turf. Irrigated lawns are highly attractive to the feeding larvae.

When is lawn armyworm most active in Australia?

Peak activity occurs in the late summer and the early autumn. Outbreaks tend to occur after hot weather and regular irrigation. Outbreaks are common in QLD, NSW, ACT, and northern VIC.

How do I identify lawn armyworm larvae?

Lawn armyworm larvae have distinct stripes, a smooth body, and curl into a C-shape if you disturb them. Young larvae are small and pale, whilst mid and late stage larvae are darker in colour with bold yellow, white, and dark bands.

What are the first signs of lawn armyworm damage?

Early signs of Lawn Armyworm damage include shredded leaf tips, thinning turf, and small window-paned patches. As the larvae grow, they remove whole leaves and cause brown areas to appear overnight.

Jerry Spencer

Jerry has an Hons Degree in Soil Science (1988) from Newcastle Upon Tyne University. He then worked as a turf agronomist for the Sports Turf Research Institute (STRI) until 1993.

He gained a Grad Dip in Business Management from UTS in 1999. He has held a number of technical roles for companies such as Arthur Yates (Commercial Technical Manager) and Paton Fertilizers (Organic, turf specialty and controlled release fertiliser) portfolios.

In 2013 he established Gilba Solutions as independent sports turf consultants and turf agronomists. Jerry has written over 100 articles and two books on a wide range of topics such as Turf Pesticides and turfgrass Nutrition which have been published in Australia and overseas.